Introduction to pilot and feasibility studies

There are an increasing number of published studies referred to as pilot and feasibility studies. However, there are sometimes differences of opinion as to what these terms mean.

What are pilot and feasibility studies?

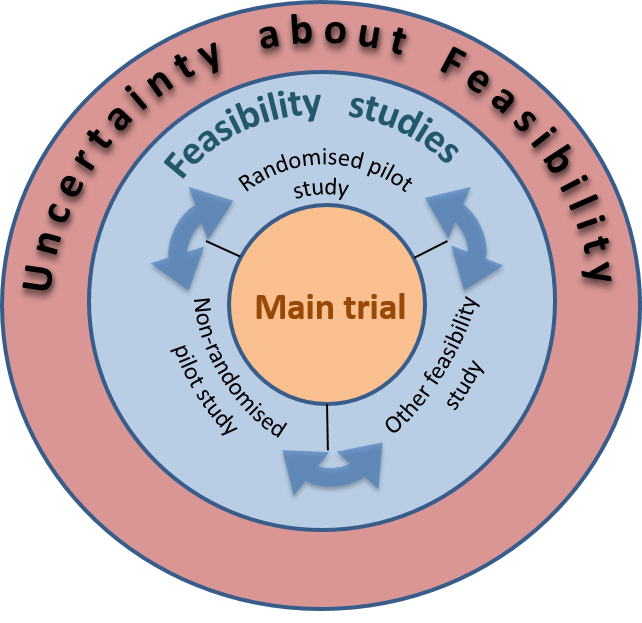

A well cited framework suggests the following definitions:

-

A feasibility study asks whether something can be done, should we proceed with it, and if so, how.

-

A pilot study asks the same question but has a specific design feature: in a pilot study a future study, or part of a future study, is conducted on a smaller scale.

The corollary of these definitions is that all pilot studies are feasibility studies but not all feasibility studies are pilot studies. This framework is based on extensive research into the use and opinion of these terms by the research community and more general definitions of the terms:

-

-

Eldridge SM, Lancaster GA, Campbell MJ, Thabane L, Hopewell S, Coleman CL, et al. Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0150205.

-

The framework figure is shown below:

Internal/external pilot studies

Avery et al define internal and external pilot studies as follows:

-

An external pilot is a rehearsal of the main study where the outcome data are not included as part of the main trial outcome data set.

-

In an internal pilot, the pilot phase forms the first part of the trial and the outcome data generated contribute to the final analysis (unless major changes to the protocol are needed).

-

Avery KNL, Williamson PR, Gamble C members of the Internal Pilot Trials Workshop supported by the Hubs for Trials Methodology Research, et al. Informing efficient randomised controlled trials: exploration of challenges in developing progression criteria for internal pilot studies. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e013537.

The choice of design (internal vs. external) should be pre-specified to avoid bias that may result from a decision to include/exclude data from the pilot phase made after pilot data are available. External pilot studies allow for greater flexibility to change the trial design for the main study once the pilot is complete, whereas internal pilot studies may be more efficient if investigators only want to look at the feasibility of aspects such as recruitment that will not change trial design. For more information on this efficiency, see the following paper:

-

Wittes J, Brittain E. The role of internal pilot studies in increasing the efficiency of clinical trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1990. 9(1-2): 65-71

Definitions of pilot and feasibility studies by funders

The definitions in the framework above have been adopted by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research and the Health Research Board in Ireland to guide researchers applying for funding. The latest update of the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance references these definitions too. We recommend the definitions from the framework because of their simplicity and grounding in robust research.

Incorrect use of the terms pilot and feasibility

Some reviews, as listed below, have highlighted that sometimes a small underpowered effectiveness study is labelled as a pilot or feasibility study. There is therefore a need to raise awareness of the difference between a pilot study that is designed to clarify areas of uncertainty, and a small underpowered study labelled as a pilot that does not comply with definitions and is not reported according to the CONSORT guidance:

-

Campbell MJ, Lancaster GA, Eldridge SM. A randomised controlled trial is not a pilot trial simply because it uses a surrogate endpoint. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2018;4(1):130.

-

Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, Cheng J, Ismaila A, Rios LP, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10(1).

-

Chan CL, Leyrat C, Eldridge SM. Quality of reporting of pilot and feasibility cluster randomised trials: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11).

-

Eldridge S, Kerry S. ‘What is a pilot study?’ in ‘A practical guide to cluster randomised trials in health services research’. Chichester: John Wiley; 2012. p. 179-85.

-

Billingham SA, Whitehead AL, Julious SA. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom Clinical Research Network database. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13(1):104.

Examples of pilot and feasibility studies

Below are some examples of well-conducted and well-reported pilot and feasibility studies:

-

Ashworth J, Cornwall N, Harrisson SA, Woodcock C, Nicholls E, Lancaster G, et al. Proactive clinical Review of patients taking Opioid Medicines long-term for persistent Pain led by clinical Pharmacists in primary care Teams (PROMPPT). A non-randomised mixed methods feasibility study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2025;11(1):53.

-

Merchant A, Kaur R, McCray G, Cavallera V, Weber A, Gladstone M, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of implementing the Global Scales for Early Development (GSED) package for children 0-3 years across three countries. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2025; 11(1):18.

-

Palmier-Claus J, Duxbury P, Pratt D, Parker S, Sutton C, Lobban F, et al. A mental imagery intervention targeting suicidal ideation in university students: An assessor-blind, randomised controlled feasibility trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2025;191:104780.

-

Deary V, McColl E, Carding P, Miller T, Wilson J. A psychosocial intervention for the management of functional dysphonia: complex intervention development and pilot randomised trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2018;4(1):46.

-

Sosnowski K, Mitchell ML, White H, Morrison L, Sutton J, Sharratt J, et al. A feasibility study of a randomised controlled trial to examine the impact of the ABCDE bundle on quality of life in ICU survivors. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2018;4(1):32.

Why do a pilot or feasibility study?

The purpose of performing pilot and feasibility studies is to give your research the best chance of success. When developing an intervention, the U.K. Medical Research Council (MRC) suggest that a series of pilot or feasibility studies may be needed to target each of the key uncertainties in the design, before moving on to a definitive evaluation.

A pilot or feasibility study in advance of a future definitive study is helpful to investigate areas of uncertainty about the later definitive study, for example, checking participants can be recruited and retained, testing the study protocol, estimating parameters for a sample size calculation for the future definitive study, and exploring potential outcome measures. Assessing feasibility in this way ensures that fewer problems are likely to be encountered in the definitive study. This encourages methodological rigour and higher quality definitive studies.

From a practical point of view, funders often require pilot or feasibility studies to determine whether a definitive study is likely to succeed and hence be worth funding. Moreover, funders often expect applicants to use data from the pilot or feasibility study to plan study duration, number of sites etc.

For further reading on why to do a pilot or feasibility study:

-

Lancaster GA, Dodd S, Williamson PR. Design and analysis of pilot studies: recommendations for good practice. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2004;10(2):307-12.

-

Thabane L, Ma J, Chu R, Cheng J, Ismaila A, Rios LP, et al. A tutorial on pilot studies: the what, why and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10(1).

-

Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, Lancaster GA. What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2010;10(1):67.

-

Shanyinde M, Pickering RM, Weatherall M. Questions asked and answered in pilot and feasibility randomized controlled trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2011;11(1):117.

-

Bugge C, Williams B, Hagen S, Logan J, Glazener C, Pringle S, et al. A process for Decision-making after Pilot and feasibility Trials (ADePT): development following a feasibility study of a complex intervention for pelvic organ prolapse. Trials. 2013;14(1):353.

Book chapters on pilot and feasibility studies

-

Ukoumunne, OC, Eddy S, Warren FC. How to use feasibility studies to derive parameter estimates in order to power a full trial. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods. Richards, DA, Hallberg, IR. (eds) 2nd. London: Routledge. 2025 (In press)

-

Giangregorio L, Lancaster GA, Thabane L. Chapter 13 Overview of feasibility studies including pilot studies. In Complex Interventions in Health: An Overview of Research Methods. Richards DA, Hallberg IR, Meyer G, Köpke S, Woodford J, Wengström Y, Estabrooks C, Wallin L. (eds.) 2nd edition. London: Routledge. 2025 (In press)

-

Li G, Bai X, Lancaster GA, Thabane L. Users’ guide to the surgical literature: How to assess a pilot trial in surgery. In Evidence-based surgery: understanding and interpreting the surgical literature. Thoma A, Sprague S, Voineskos SH, Serrano PE, Goldsmith CH. (eds.) 2nd edition. Heidelberg: Springer, 2025.

-

Eldridge S, Kerry S. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. In Eldridge S, Kerry S. A Practical Guide to Cluster Randomised Trials in Health Services Research. Chichester: John Wiley; 2012